Are researchers writing more, is more better and who should be an author?

The concept of some kind of ‘literature inflation’ in science has interested me for a while. The idiom ‘publish or perish’ suggests that researchers will increase their output in order to obtain positions and promotions. And if a researcher’s productivity is measured by their publication output, shouldn't we all be writing more papers?

Similarly, if we should all be writing more, then wouldn't some people start publishing two (or more) papers, when one would be adequate? This idea of ‘salami slicing’ to inflate outputs would be an understandable strategy if researchers were all trying to increase their output.

A new study by Daniele Fanelli and Vincent Larivière (2017) has a new take on the above questions, by asking whether researchers are actually writing more papers now than they did 100 years ago. They used Web of Science to look for unique authors (more than half a million of them) and determine whether the first year of publication and the total number of publications resulted in an increasing trend.

The trend line for biology (bi) is very stable at around 5.5 publications whether you started publishing in 1900 or 2000 (note that earth science es and chemistry ch do both increase dramatically).

However, they found that the number of collaborators is increasing, and so they adjusted publication rates for co-authorship. Their finding was then that there is no increasing trend in researchers publishing. This then poses another question. Who are these people that are publishing so much more than 5.5 publications, and are they unfeasibly prolific?

If we are all writing the same number of papers, are some authors unfeasibly prolific?

This was the question posed in a study that examined prolific authors in four fields of medicine (Wager et al. 2015). This publication piqued my interest as it turns out that they decided that researchers with more than 25 publications in a year were “unfeasibly prolific” as this would be the equivalent of “>1 publication per 10 working days”. Their angle was to suggest that publication fraud was likely, and that funders should be more circumspect when accepting researchers productivity as a metric. Looking back through the peer review of this article (which is a great aspect of many PeerJ articles), I’m astounded that only one reviewer questioned the premise that it’s unfeasible to author that number of papers in a year.

I have not published >25 papers in a year, but I know people who have and I do not question that (a) it is possible and (b) that they really are the authors. Firstly, the idea that prolific authors constrain their activity to “working days” is naïve. Most will be working throughout a normal weekend, and working in the early morning and late evening. A hallmark of a prolific author would be emails early in the morning and/or late at night. This gives you an indication of their working hours, and how they are struggling to keep up with correspondence on top of writing papers. Having authored >20 papers this year (2017), I can attest to the fact that it’s a lot of work and that it would not be unfeasible to have authored five more.

Authorship of a publication is often the result of several years of work. Thus, publications that I co-authored in 2017 frequently had research conducted in 2014 or earlier. For example, one of the publications, Measey et al (2017) is the product of aSCR work that started in 2009, funded in 2011 with fieldwork in 2012, and required the development of software for analysis by Ben Stevenson in 2015, before it could be completed and submitted. Thus, from my perspective, when I look at authoring a lot of publications it reflects the activity of the initial concept for the work, raising of money, conducting the field work or experiment, analysing the data and then writing it up (with the subsequent submission and peer review time). Thus, publications in 2017 result from a lot of work done for 3 or more years.

Who should be an author?

There is an increasing number of journals that now give clear instructions on who should author a paper, and these have been formalised by the ICMJE. For some time, I have explained to MeaseyLab members that authors need to participate in at least three of the following five points before they can be considered for inclusion in the author line.

- initial conceptualisation for the work (hypothesis and/or question)

- raising of money (which often involves writing and submitting several research proposals)

- conducting the field work or experiment (the hard slog that many people will recognise)

- analysing the data (often much more difficult than anyone realises)

- writing it up (see lots of postings on this blog about the many requirements of writing)

It’s worth taking some time to think through each of these aspects of a piece of scientific work, especially when considering your own authorship. One point that students (in particular) often fail to recognise is that by the time they start on day 1, the first two points in this list are often completed. It’ll only be much later, when you have to raise your own money to conduct research, that you will appreciate all the work that went on before day 1.

My list is different from that of the ICMJE, but not mutually exclusive. They appear to have placed all of my first 4 categories into 1 and then added “final approval” and “accountability” as extra requirements. While I agree with the ICMJE list, I wouldn’t add “final approval” and “accountability” to my list above as these are journal requirements that all authors must meet for any publication. By the time authors arrive at this point, their name has already been included on the submitted manuscript throughout peer review.

Is writing a lot of papers a good strategy?

This is a question of long standing, and one that you may find yourself asking at some point early on in your career. I'd suggest that the answer will be more about the sort of person that you are, over any strategy that you might consciously decide. If you tend toward perfectionism, this will likely result in fewer papers that (I hope) you'd consider to be of high quality. If on the other hand your desire were to finish projects and move on, you'd be more likely to tend toward more papers.

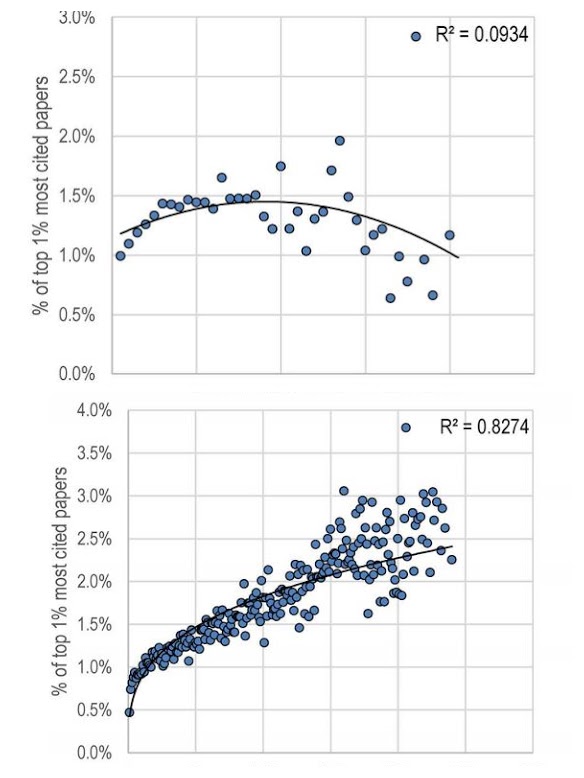

Given that the 'best' personality type lies somewhere in the middle, you can decide for yourself whether you identify with one side more than the other. But which is the better strategy? Vincent Larivière & Rodrigo Costas (2016) tried to answer this question by considering how many papers unique authors wrote and seeing how this relates to their share of authoring a paper in the top 1% of cited papers. Their result showed clearly that for researchers in the life sciences (bottom graph below), writing a lot of papers was a good strategy if you started back in the 1980s. However, for those starting after 2009, the trend was reversed with those authors writing more papers less likely to have a smash hit paper (in the top 1% of cited papers). Maybe the time scale was too short to know. After all, if you started publishing in 2009 and had >20 papers by 2013 (the inflection point of the curve in top graph below) then you have been incredibly prolific (only 19 authors from what I can see).

One aspect not considered Larivière & Costas is that becoming known as a researcher who finishes work (resulting in a publication) is likely to make you more attractive to collaborators. Thus, publishing work is likely to get you invited to participate in more work. Obviously, quality plays a part in invitations to collaborative work too. Thus pulling the argument back to the centre ground.

If you find yourself becoming pre-occupied about which is the best strategy for you, I'd suggest that you get back to finishing what you were writing before you got distracted!

If more is being published, will Impact Factors increase?

Yes. A number of years ago (October 2013), I asked David Green (Global Journals Publishing Director for Taylor & Francis Group) whether there was an inflation rate for Impact Factor of journals. He responded that it ran at around 5%, but then didn’t come up with a source for this information when I followed up.

Of course, it’s not just that more is being published, but the number of citations within every paper is increasing over time. Who and how should you cite? That's the subject of another blog.

.JPG)